By Megan S. Hollinger

For the past two fall terms, I have been fortunate to teach Carleton University’s The Holocaust: Historical and Religious Dimensions, also known as the Holocaust Encounters course, generously funded by CHES. My first opportunity to teach undergraduates, the Holocaust Encounters course has continuously provided me with a rewarding and fulfilling experience. Holocaust Encounters is cross-listed under Carleton’s Religion and History departments, meaning it must include both historical lessons and religious studies perspectives.

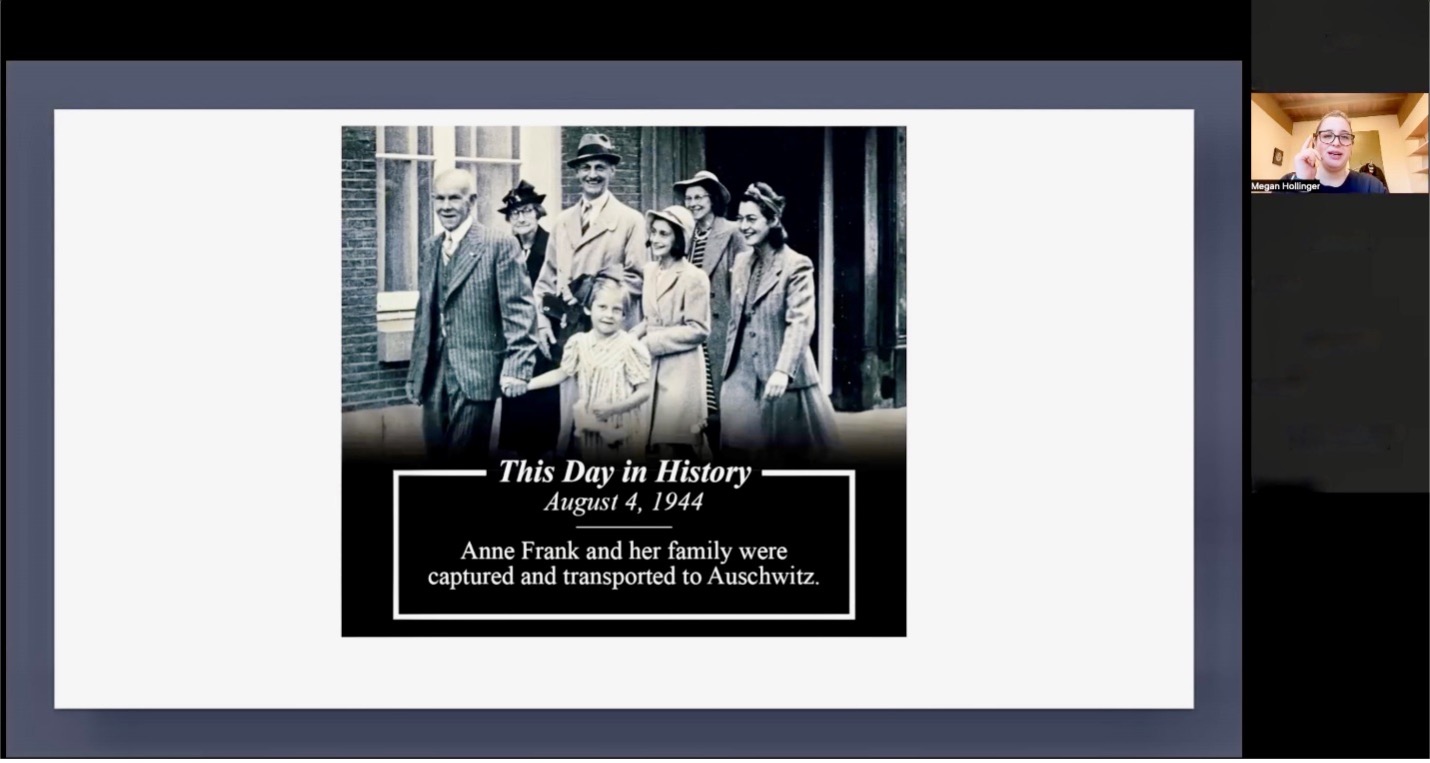

Holocaust Encounters welcomes 60 to 70 students each fall and takes them on a journey through time and space to understand not only the events and circumstances surrounding the Holocaust but, as the official course title suggests, the historical dimensions that enabled it to happen and unfold the way it did. We also examine various religious and theological positions and responses to the Holocaust from the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim worlds. My impression has thus far been that students find this course to be both challenging intellectually and emotionally, with exposure to a diverse body of scholarly work on antisemitism and the Holocaust, as well as survivor testimonies and visual materials.

I believe it is integral to incorporate a historical overview of anti-Jewish hatred into the course. We begin by learning about the history of Christian anti-Judaism, and we consider the origins of various anti-Jewish tropes, stereotypes, and accusations rooted in the socio-cultural, economic, and religious complexities of the early Church and Medieval periods. We then cover the evolution of anti-Judaism into racial antisemitism and discuss how anti-Jewish hatred normalizes and popularizes itself over time. Additionally, we learn about the contextual differences between Jewish communities in Western and Central Europe versus Eastern Europe and Russia. No matter the lesson, I always stress the nuances of Jewish identities through time and space, so students develop a better idea about the Jewish people and their experiences leading up to the Holocaust.

Following our journey through the historical context, we discuss the rise of the Nazi Party to power and how the Nazis implemented their mission to eliminate the Jews from what they saw as a future pan-European, Aryan empire. After understanding the Holocaust and its historical background, we examine the religious responses and perspectives mentioned earlier. Examining these responses is crucial to understanding the complicated human emotions tied to the Holocaust, not only for victims but also for rescuers and perpetrators.

We end the course with a lesson on Holocaust denial and antisemitism in the contemporary world, learning about how some weaponize the Holocaust in different contexts to continue victimizing Jews and minimizing their history. Students develop their critical thinking and scholarly sensitivity through learning about different religious and secular responses, as well as through our discussions on Holocaust denial and distortion.

I have found, through my work on combatting antisemitism, as well as through educating young minds about the Holocaust, that creating an emotional response to the subject matter and to victims heightens the students’ receptivity and, ultimately, their desire to identify contemporary antisemitic rhetoric and question its validity. I have, therefore, made sure to include a variety of survivor testimonies and guest speakers to engage the students and increase their emotional responses and relation to the topic. I was able to partner with Carleton’s Zelikovitz Centre for Jewish Studies, who kindly assisted in making public my lectures on Muslim and Arab responses to the Holocaust. We were privileged to hear from renowned experts on this topic, including Dr. Mehnaz Afridi of Manhattan College and Dr. Meir Litvak of Tel Aviv University.

In addition to scholarly experts, we heard live testimonies from children of survivors, including Annette Wildgoose and Bruria Michman. This past fall, we also heard from Holocaust survivor Vera Gara, who kindly and bravely shared her experiences with us and openly answered the students’ questions. My impression is that these guest lectures are one of the most meaningful aspects of the course for the students; the students always remark on how hearing personal accounts and different perspectives opens their eyes and hearts.

I have emphasized testimonies and stories in this course because of their power to bring meaning to the Holocaust. However, witnessing the sense of empathy and compassion for the tragedy of the Holocaust that my students developed reinforced for me that Holocaust education should emphasize creating connections and building empathy. These types of outcomes are critical given the current spike in antisemitism in Canada and globally. Even regarding current world conflicts and tensions, I witnessed a sensitivity in my students that deserves to be noted. While the students’ integrity and strength of character should no doubt be commended, I also credit the nature of such a course to their reactions and desire to learn about complex topics with open minds and hearts.

As I go forward teaching Holocaust Encounters, I hope to continue working on empathy and compassion-building to empower students to care about the Holocaust and human tragedies around the world.