By Dr. Phil Emberley

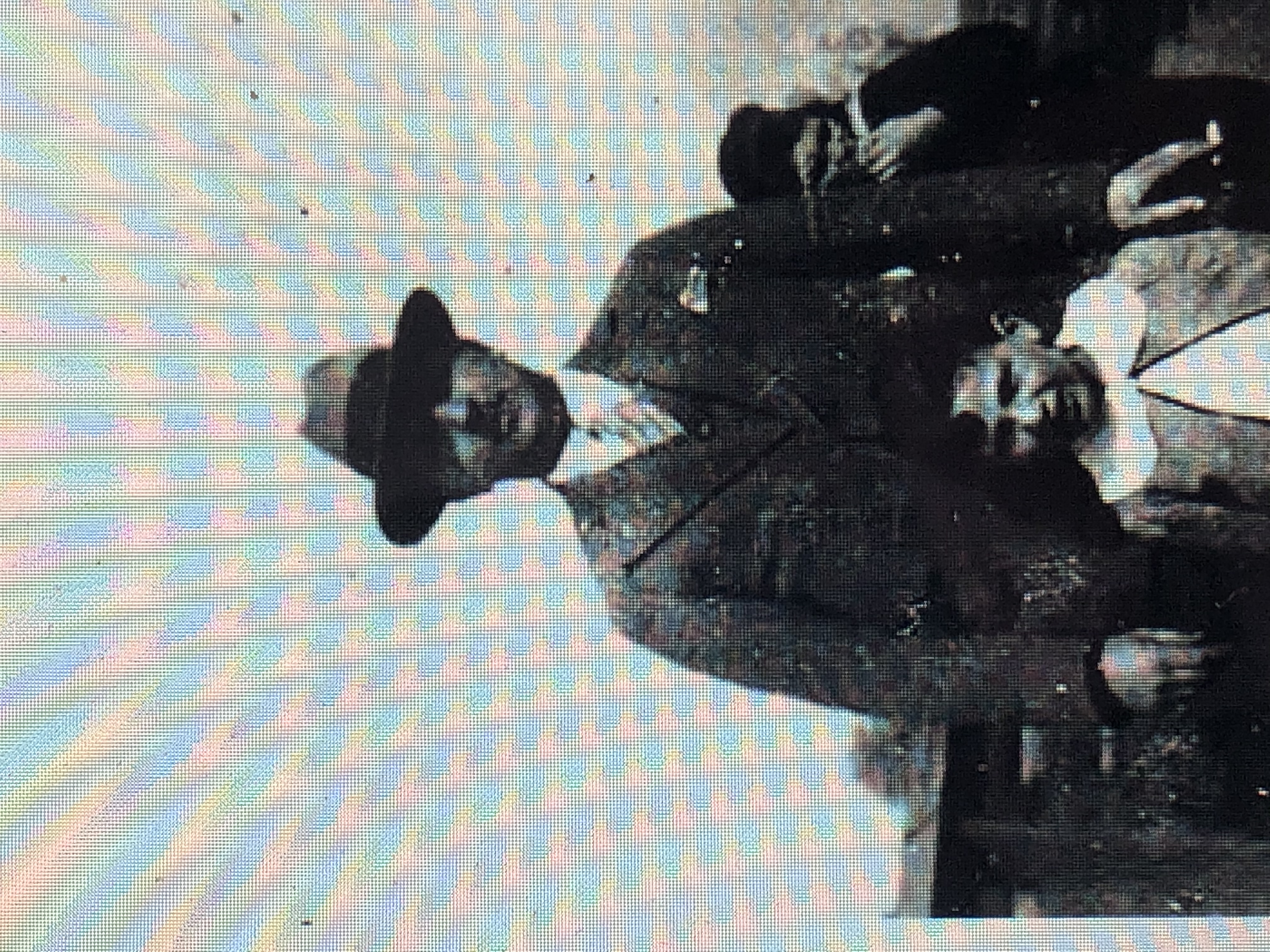

I am the son of Dieter Werner Eger, born November 11, 1925. On August 25, 1939, my father, having bid farewell to his sorrowful parents – Berthold Eger and Minna Eger – boarded a train from his hometown of Frankfurt am Main, Germany, with a destination of the United Kingdom. He was under the guise that this was a vacation and that in the near future, he would be reunited with his parents; unfortunately, his parents knew the exact opposite. Dieter had lived through a dreadful decade in Nazi Germany, having been expelled from school and increasingly faced antisemitic threats. It started with bullying at school and was soon followed by earlier and earlier curfews; ultimately, he was housebound once it became too dangerous for him to leave. He once snuck out with his father to a professional soccer match, and fearing being discovered, both signaled the Nazi salute at the start of the game.

The Kindertransport was a remarkable mission in a number of ways. The British government under Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain saw the rapidly deteriorating conditions for Jewish people in Europe and the prospect for future human suffering and turmoil especially after the events of Kristallnacht. This spurred the government to act in an effort to rescue Jewish children. Also remarkable was the will of Jewish parents to dispatch their children, knowing fully that this would be their last farewell; there can be no doubt that these parents had a clear vision of what lay ahead and that the lives of their children would continue to be jeopardized if they remained in Germany.

While the initial intent was that the Kindertransport would continue as long as the British people were willing to foster the children, the program ended with the commencement of World War II by which time about 10,000 children had been evacuated.

On the evening before his bar mitzvah rehearsal – November 9th, 1938, which was the infamous Kristallnacht – Dieter’s synagogue was burned to the ground. Upon arriving in England, he converted to the Anglican church as part of his effort to establish a new persona. He would later become a British citizen and, to many who knew him later in life, he was the quintessential Brit, and, in fact, his last job was with the British Consulate in Vancouver.

My father was fostered by an individual who operated a home for orphaned boys. He soon became employed as a farm hand, working for minimal pay. As soon as he was eligible, he enlisted in the British Army and changed his name to Dennis Walter Emberley. My father was one of the majority of the Kinder who never saw their parents again. All of his relatives, except for one uncle, perished in the Shoah. His parents initiated the paperwork to evacuate to the United States, but for some reason this never came to be. Each year my father would secretly remember Kristallnacht in his journal; the event had an indelible impact on his life.

Following the war, because of his ability to speak German, Dennis was deployed to Germany where his duties included transporting German prisoners of war. It was on a train in 1953 that he met my mother, Ursula Warmbier, a German from Berlin who was employed by the United States Embassy. Following their marriage in 1955, they emigrated to Canada, where my father continued his military service as a senior officer with the Canadian Armed Forces. For them, Canada was the land of opportunity, and a good country to raise their family of two sons, me and my brother, the late Dr. Peter Emberley. A few years later, Dennis converted to Catholicism, the religion of my mother.

Dennis, who died on July 15, 2006, would serve as a senior officer in the Canadian Armed Forces with tours of duty that included with the United Nations in the Gaza Strip from 1959 to 1961 as well as at Lahr, Germany, an important NATO defence installation. His ability to converse fluently in German and English made him an important asset in optimizing Canadian and German relations in Lahr. He received the Order of Military Merit – the military equivalent of the Order of Canada – and in 1990 was made a Member of the British Empire (MBE) for service to the British Commonwealth. He is one of a select few Canadians to have been awarded both honours.

It was only after my father suffered a psychiatric episode in 1977 that I would learn of his traumatic past. His life was exceptionally compartmentalized in that he did not let his past influence his professional demeanor. Unfortunately, this also meant he did not discuss his past with his sons, but rather spoke through his journal that he wrote daily.

I cannot fully describe how powerful an influence this family history has had on me. As a young adult, that influence was minimal, but as I grew older, I felt such an intense feeling of sorrow as well as an understanding of any shortcomings I perceived in my father. I felt compelled to talk about the Holocaust, to tell my father’s story, and to raise a son, Brayden, who also realizes the evils of Jewish persecution that would compel a person to change their name and their religion for self-preservation. As the parent of a teenager, I asked myself, “Could I ever put my child on a train, never to see him again?”

How could I not?